(Published in Small Craft Advisor Magazine)

(Published in Small Craft Advisor Magazine)I had been so proud! I’d been invited to be one of two kids to represent our local sailing club as skippers in a multi-club regatta held by another sailing club down on Long Island’s Great South Bay. In a Beetle Cat, a class of boats I had sailed in, but never skippered before.

And now, out of 14 boats, we were last. Not just last, but dead-seemingly-miles-and-miles-behind, last.

All I wanted was to be at home, buried under blankets in the deepest, darkest, corner of my closet, so I could cry my brains out.

. . .

My family, avid cat boat sailors, moved from Duxbury, Massachusetts down to Huntington, Long Island when I was six. We moved lock, stock and barrel — but not boat. Apparently, no one here in this new place sailed Beetle Cat boats (one sail, mast way up forward).

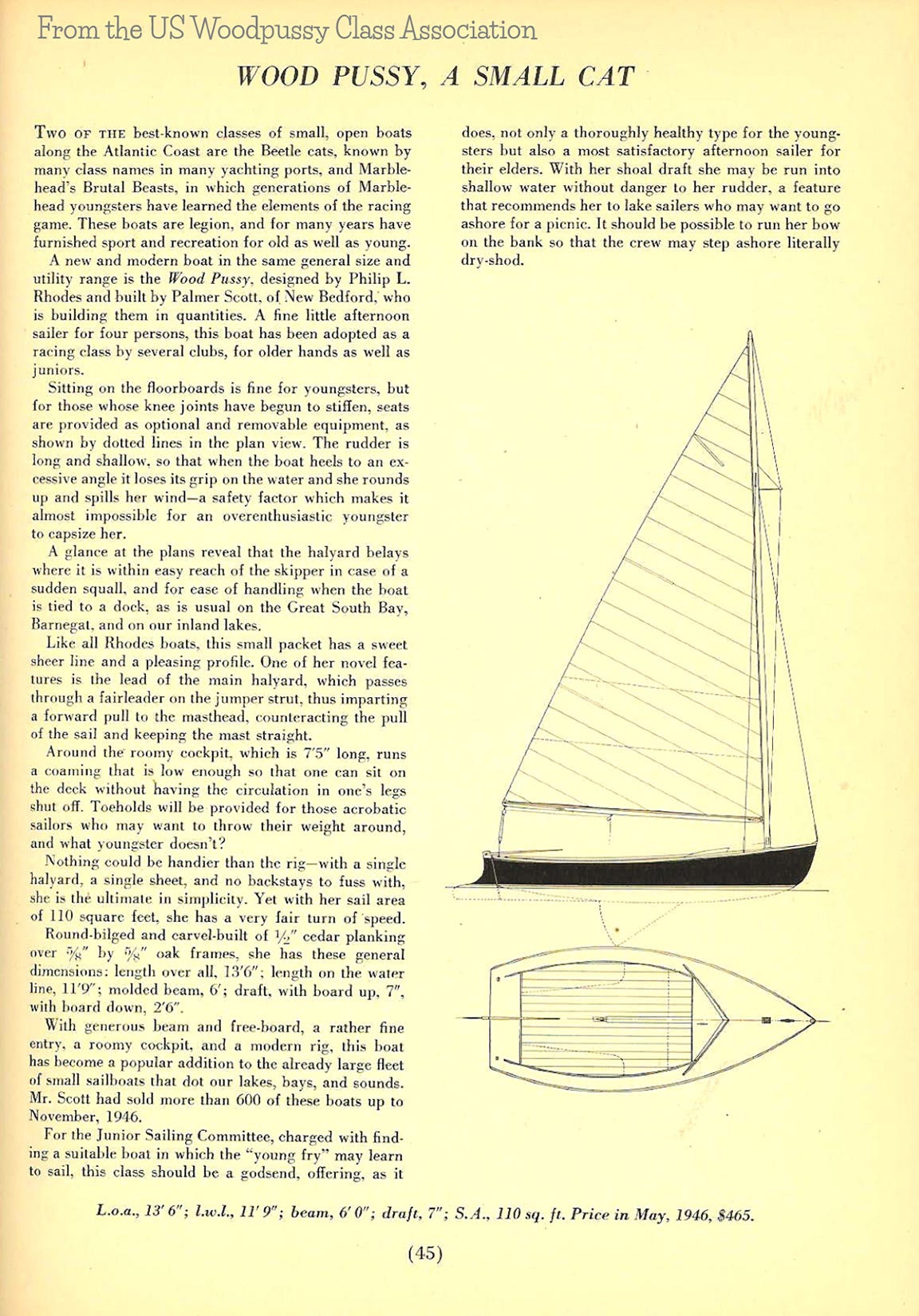

The only small boats that came close to the beloved one we’d left behind were the 13.5’ Woodpussys*. Don’t laugh! I bet you didn’t know that the nickname for skunks is woodpussy! Technically still a cat boat, but less beamy (wide).

Unlike the Beetle Cat, our new boat had a triangular, Marconi rig sail. No gaff, no rings sliding the sail up the mast. A handy single halyard. A simple, sweet design.

So I grew up sailing the little skunk, our sassy, pretty, bright red Woodpussy.

. . .

I took one look at that impossibly wide boat sitting there so calmly, floating at the dock, waiting for us to hop in and take it for an adventure, and I just wanted to escape back home.

All the stories that I’d heard since leaving Duxbury about our long-gone, fabled boat, gustily told over the dinner table, rushed through my mind. As if I’d been kicked in the guts, it hit me that not one of those tales actually helped me know how to sail the damn thing.

All I could think was that this thing was just a fat, flat, rounded bathtub, with a huge sail extending past the stern. And what was I supposed to do with that gaff? Dread filled me to the brim.

Too late now. We were committed.

We started to get ready. My crew, my best friend Holly, was completely unperturbed. I held my fear in check — barely — but was still dazed by the understanding that, for me, it would be like riding a mustang for the first time.

All the other skippers looked happy and relaxed, confident. They’d obviously handled these wild things before.

I was not — not! — going to give up.

We finished setting up the unfamiliar lines, checking the tiller, rudder, centerboard, and emergency stuff under the deck.

I got situated. Holly took up her position. We pushed off.

We fooled around, clumsily practicing tacking, getting used to the feel of the boat, on our way to the starting line. Talk about immediate immersion learning!

Most of the other kids were older than we were — 17, 18, to our 13 and 14 year old selves. Some of them sniggered and made remarks like ‘who let the babies in?’

I detest arrogance. I could feel the hairs on the back of my neck rise. Ever the calm one, Holly patted my hand and said, “Never mind, they’re just full of themselves, let’s just keep practicing.”

So we did. It became painfully clear that we were grossly unqualified. Nevertheless, silently, eye-to-eye, we nodded, agreed to give it our best.

The gun went off.

We’d lucked into a good starting position.

Away we went.

We managed to keep up with the pack for the first leg, a pretty easy beam reach. My confidence swelled a little. We swung around the buoy into a long down-wind leg.

The wind, mild before, had picked up a bit as we crossed the starting line. Now it continued to gather force. By the time we rounded the first buoy, we were butts-out on the rails.

I thought this downwind leg would be fun, so I let the sail out almost as far as it would go. We lowered the peak to increase the bag in the sail, and raised the centerboard to reduce drag. Even leaving a small centerboard fin to help with steering the boat, we still picked up speed so fast both Holly and I were almost knocked flat.

It felt as if we were beginning to plane! We picked ourselves up and rushed to sit as far back as we could get. Even with all our weight astern, it was a hard job keeping our boat’s nose up out of the waves in front of us. Holly on the main, me on the tiller. I had to spill some of the wind, but even then it was a chore to keep the bow from drilling a hole right down to the bottom.

It seemed like a century passed before we rounded the next buoy.

I took it so fast and so close that if the boat itself had screeched, I wouldn’t have been surprised. Holly trimmed the sail perfectly. No luff; not too tight. It was going to be a tight sail all the way to the finish line.

We remembered to tighten up on the peak. Our hands and arm muscles felt like they were on fire. Thankfully, even though the wind was now howling, it looked like we’d only have to tack maybe three times in the beat to get home.

By now the boats were in two groups — the leader and five or six others in the front pack, and the others scattered farther behind us.

We were in the last part of the first pack. The finish line seemed impossibly far away.

It was right then that I made the most colossal mistake.

I’d been accustomed to sailing in Cold Spring Harbor. Key word: harbor. Where the wind doesn’t just go neatly la-la-la across the body of water without interruption.

Instead, the wind bounces off the land and back out again. You can use the currents and eddies of air produced by those bounces, if you can read them on the water or by your tell-tale. These short bursts and low shifts of wind allow you to maneuver right on past boats further from the shore.

We were pretty far out in the Great South Bay. I didn’t know the air there, or the way the tide moved. The shore seemed really far away. I decided just to take the same route as the lead boat, following its wake. The other boats were clustered together, with us slightly behind.

Choosing to mimic the path of the lead boat was a complete disaster.

See, once a boat moves through a space, the wind shifts — sometimes a little, sometimes a lot. By the time I tried to sail into the wake of that lead boat, the air was so messed up by all those boats having tripped on through, there was no steady flow.

I lost the wind, and every bit of my momentum.

I fell further and further behind. Boat after boat slipped right by us on new gusts of clean wind. Jeering. I couldn’t seem to pick us back up again.

We were so far behind, we had to get out of that bad air! I considered getting closer to the shore, but let the idea go in a flash of fear that it would take too long to angle over. Better to just follow.

We were last.

I just wanted this race to be over. I could feel my shoulders slump, my head begin to hang down. I felt defeated.

Holly was beside herself, trying to get me to go inside, knowing we should take advantage of the shore. But nooo, fear had me by the unmentionables, and I refused any advice she tried to give me.

She suggested.

She laughed, lightly, kindly.

Gently saying do this, do that.

What if you… why don’t we…

Finally, she yelled right in my face, “Angela! We’re last!

Go inside! What do we have to lose now?”

I popped out of my fear-daze, did what she suggested. We gradually picked up speed, and at last we slid across the finish line.

We were so late that the guys on the regatta boat shouted ‘thanks for keeping us out here so long! About time you got in!’ as we sailed by.

I felt my shoulders climb up around my ears in shame.

Tired of pushing and stressing, we let most of the air out of the sail. We crept slowly over to the docks. No one was there except a couple of race officials. And my mother.

I wanted to die on the spot. I felt so embarrassed, so ashamed, so humiliated.

Holly was outwardly calm, but I could see that even she was on the verge of tears, too.

As we reached the dock and secured the lines, my mother — my hero mother! — ran over, flew into the cockpit, swept Holly and me up into a bear hug I’ll remember the rest of my life.

“You did it! You did it! I’m so proud of you!”

Holding us out to her sides so she could see us better, she had the face of the most lit-up angel I’d ever seen. Holly’s tears disappeared into a timid smile as my mother hugged her.

Incredulous, I broke down. Huge tears jetted out of my eyes. My belly felt like exploding. I pushed away, feeling paralyzed with confusion. Swiping my eyes with my sleeve, hands on hips, I let my anger and humiliation out.

“But … but … we came in last! What exactly do you think we did??? Last! What about that are you ‘so proud’ of?”

She pulled us both down into the cockpit, sitting cross-legged with us. Gave me the stink eye, and then laughed, throwing her arms up.

“Don’t you get it? You’re only 13! But you traveled to a new place, climbed into a new boat the likes of which you’ve never skippered before, had the smarts to practice a little before the race, and not only entered into the race, but finished it!

Who cares that you came in last? You didn’t quit!

You gave it your best, and you made it back across the line!

You didn’t quit!”

I let that percolate for a minute.

Glaring at her, I shouted, “You mean, I could have just quit? I could have just said, this is too hard, I don’t know how to sail this fat tubby thing? And I could have sat here watching everyone else race? You really think I’d have QUIT????”

“No, honey,” she said softly, “I knew you wouldn’t quit. And I knew Holly wouldn’t either. I’m so proud of you.”

Just as the thought of “I did do it!” crossed my mind, the sun peeked out in a last show of orange glow at horizon’s edge. I know, serendipity-do, right? Well, it did. It was gorgeous.

We finished getting the boat shipshape and went home.

And instead of climbing into the backest part of my closet, I clomped downstairs and sat around the table in the kitchen with everyone — mother, father, older brothers, Holly, little brother, dogs, and me.

We went over every lick of the race.

They helped me understand that, not only was following someone’s wake bad news (as if I didn’t know by then); and that I needed to ditch my fear and get off my defensive I-know-how horse, so people could give me ideas; but most importantly, that I was not a loser, even though I lost the race.

I slowly let myself be happy.

Even though I’d come in last.

Last does not mean loser.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Thanks for reading my story — I hope you enjoyed watching as I stumbled through one of the most important life lessons I ever experienced. I hope it inspires you to remind yourself of your own value and worth, no matter what.

-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-

Last Does Not Mean Loser

© Angela Treat Lyon 2023

Image: Almost Home

© Angela Treat Lyon 2023

Read about Beetle Cats here: https://beetlecat.com/beetle-cat/

* Woodpussys, designed by Philip Rhodes, just happened to be built by my uncle, Palmer Scott, in New Bedford, MA.